The Haïk's Enduring Allure

|

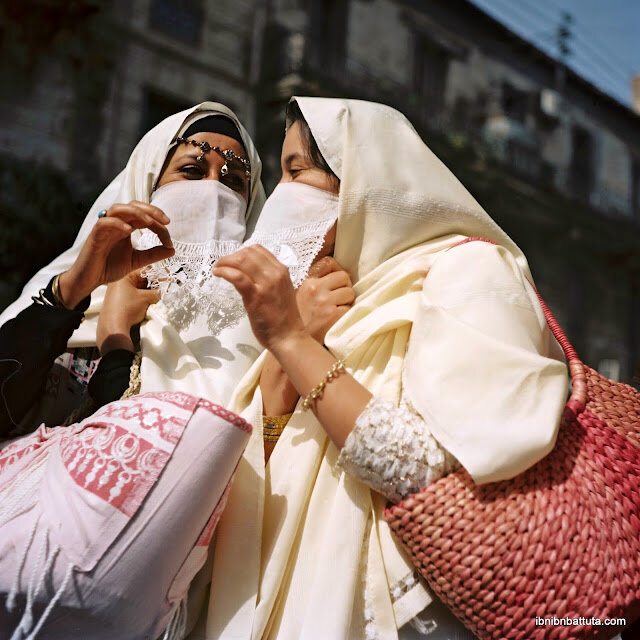

| Many Algerians consider the haïk to be just as much a symbol of the nation as its physical monuments. |

That was my conclusion after the latest outing, one sunny Saturday in late March, by the "Belaredj" collective, the cultural group behind the haïk events I tagged along for twice last year. (To learn more, see "Celebrating the Haïk, and Debating an Algerian Icon" and "The Haïk: A Symbol of Algeria's Revolution".)

The unique allure of the haik—the traditional women's dress of Algeria, now rare on the streets of Algiers—was in full evidence at this spring's outing, organized as always by Belaredj's founder, local performance artist Souad Douibi. Souad's other recent events (which she bills as "performances" rather than mere cultural festivals) had garnered increasing attention, as photographers—myself included—inundated Algerian social media with modern images of this classic symbol. In a country so fixated on its history, such images hold particular power, and motivated more than a few photographers to attend this spring's event.

The morning's rendez-vous point was the Grande Poste, the brilliant white central post office of Algiers. My Rolleicord and I were ready, but we sure weren't alone. Upon arriving, I immediately noticed that camera-toting amateur photographers appeared even more numerous than the haïk-clad subjects they hoped to photograph, a peculiar reversal of the ratio at previous events and the first of many signs that day that the Belaredj collective risked becoming the victim of its own success.

|

| Souad Douibi, at right, and her friend Ghazia head the tight circle that leads the Belaredj collective. |

At 10 o'clock sharp, a tight cluster of white-clad women streamed out of the Grande Poste and toward the subway. A few men in the traditional local sailor outfit, known as shanghaï, marched with them. Bystanders stopped and grinned, giddily cheering, and photographers jogged alongside the group, snapping away. Leading the pack was Souad, who shouted back to her charges, "Don't stop! Remember, this is a performance, not a photo shoot!"

|

| The Belaredj group in haïks on the Algiers metro. |

On board, a few veterans chuckled as the younger women in haïks, unaccustomed to wearing the garments, consulted their reflections in the darkened train windows to adjust their wraps. A few stops down the line, Souad's order to disembark filtered quickly along the clusters of women in white, scattered throughout the train cars.

|

| Belaredj devotees include several men, like this one in an adapted shanghaï, a traditional sailor's outfit. |

But the local men's reactions were the best—so good, in fact, that I soon started focusing my attention and my camera more on them than on the women in haïks. For a second, many men simply gaped, slack-jawed, incapable of comprehending the sight before their eyes on this random Saturday morning. Then they snapped out of it, and brightened like I've never seen. Whole cafés full of men emptied onto the sidewalk to watch the women stream past, whistling, clapping, and whooping.

Sexual attraction didn't seem to be part of the equation; from the surprise on their faces I could tell the men had forgotten themselves, and were carried by a raw up-swell of nostalgia. It happened too fast to be anything but genuine. Unable to contain himself, one man stumbled from a café stoop, nearly in tears, shouting, "Ya Allah! Hada lmoment weyn nheb edjezair, ki nchouf hadou lbenat en haïks!" ("My God! This is the moment when I love Algeria, when I see these women in haïks!")

The older men in particular—who remember Algiers when every woman wore a haïk—provided me with the most magical moments of my day. One old sheikh who had been tapping his way down the sidewalk with his cane, for example, stopped mid-stream as the women in haïks sped past. After a second, his wizened old lips cracked into the slightest of smiles that communicated the most profound of joys.

|

| Dumbfounded: I soon started to focus on the men's reaction to the passing women in haïks. |

Inside, they paused for a group shot, but as dozens of local punks from around the park began streaming toward them for photos, Souad called it off, and told the group to remove their haïks. The day wasn't over, but they would wait a few hours for the situation to cool down before donning them again.

The pause, coincidentally, gave others—including a Chinese tourist and a trio of good-humored park gardeners—a chance to try on the haïk, making for some very unique images.

Full photo album: